Spotify Culture: We Ask Spotify’s VP of Engineering What It’s Like to Work There

Interviews Emma Tracey

According to Kevin Goldsmith, VP of Engineering at Spotify, the Swedish music-streaming mammoth’s success all comes down to its team culture. We sat down with the Carnegie-Mellon educated, Chicago-native at MobiConf Krakow. Over a weak coffee and prior to a strong vodka, he told us all about the fine balance between autonomy and chaos, preserving start-up culture in a large organizations, his escape from Microsoft and why failure is all part and parcel of the life of a continuous improvement organization.

[UPDATE] Kevin is no longer VP of Engineering at Spotify. in June 2015, he became CTO of [Avvo]

Our interview on Spotify Culture with Former VP of Engineering Kevin Goldsmith

Hi Kevin! Spotify uses phrases like “tribe” and “squad” and “alliance”. Our first question has to be does Spotify just not like the word “team”?

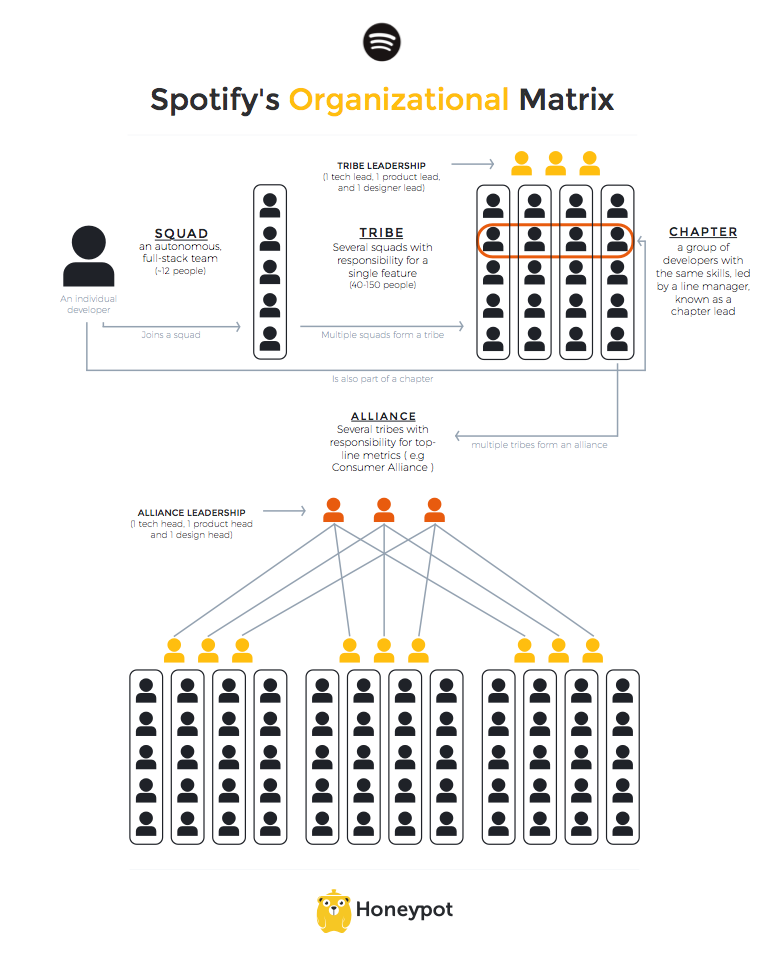

Ha! I get asked this question a lot actually. We choose these different names because any individual can be a member of multiple teams (at minimum they are a member of a squad, chapter, tribe and guild) and it all depends on the context. Honestly, we had to create these new words to be able to talk to each other.

If a new developer would join Spotify, what type of team would they join?

They would likely join a squad. A squad is an autonomous, full-stack team composed of six to twelve people, usually containing a Product Owner, UX, iOS, K&M [keyboard and mouse], QA, Android, Backend, and a Scrum Coach. Squads are essentially Spotify’s mini-start-ups with full responsibility for a single feature or component, and Scrum teams have full power to make decisions. This is the fundamental unit of Spotify’s organizational structure and is designed to optimize autonomy.

So squads are designed to give team members autonomy. How is this implemented logistically, in terms of office space and design?

Squads are housed in squad rooms with 12 desks, a chill-out area and a meeting room.

How is work divided between squads?

A squad is started to fulfil a particular mission. Missions can be open- or closed-ended. Search for example is an open-ended mission. In the case of a close-ended mission, to upgrade a feature for instance, squads dissolve once the mission is complete. Teams aren’t dependent on other teams. They don’t need to coordinate with anyone else to get their job done, so they are continually innovating.

Who is responsible for the squad?

The squad is collectively responsible. Larger organizations who are attempting to implement the Spotify model often overlook this point: individually accountable, collectively responsible.

Does Spotify have managers?

This is another common misperception. Spotify does have managers, it’s just a different perspective. Instead of having team managers, we have line managers, which we call Chapter Leads. They look after all those people with the same skillset across the squads. For example, I might be the Chapter Lead for all Android developers. The cool thing is Chapter Leads are part-time developers, they usually sit on one of the squads themselves.

What are the benefits of this vertical leadership?

Your boss is doing the same job as you, that’s a huge benefit. They can understand what you are doing day to day. The Chapter Lead also has visibility into a number of teams and can facilitate movement of people which makes the organizational structure very dynamic. Your chapter becomes your home and your boss stays your boss and your peers stay your peers no matter which squad you are on.

How does the tribe connect to the squad?

Spotify’s engineering and product organization is split into several large groups, called tribes. Multiple squads form a tribe. And Tribe Leads are the first level of full time management. The ideal size of a tribe is 40 to 150 people; 40 keeps the tribe fluid and allows for movement between squads and 150 is when you start to reach Dunbar’s number. Each Tribe has responsibility for a particular set of related features or engineering functions and is designed to encourage independent workflow and autonomy, cut decision-making bottlenecks and improve the speed at which decisions can be taken, all while keeping teams cross-functional with fluid communication.

How many tribes are there and what are some examples of how they are divided?

There are currently twelve tribes. In my organization, there are three tribes: one tribe is focused on satisfying high-intent use cases, like running and user curation. One tribe is focused on low-intent use cases, and another on product strategy. The last tribe handles the media path from ingestion from our media licensors through to playback on local devices.

How do you encourage communication between tribes?

We have guilds, these are voluntary groups which span the entire organization. Anyone can create a guild and membership is optional. We have very work specific guilds – the Java guild, the C++ guild, the Android guild. Then we have more fun guilds, like the craft-brewery guild, the photography guild. So there is both structured and unstructured guilds and they meet regularly.

Let’s talk a little about you. Before you joined Spotify, you had some experience with big companies, like Microsoft and Adobe. What attracted you to Spotify?

The funny thing was the senior leaders at Spotify approached me because they wanted some big company experience. And I liked them for everything that set them apart from big-company culture. When they sent me over the documents about the model something clicked for me. This is what I had been working towards and trying to implement at Adobe. But at Spotify it was fully realized. My first question was does it really work this way? When I visited Stockholm, I immediately saw that yes it does work this way.

You joined Microsoft in 1994. What were you doing there and how would you describe the company culture?

I joined as a software design engineer. I worked on a number of different products there but in my final role I was working as part of the Windows Media version 7.0 application team in the Digital Media Division. At that time Microsoft were famous for their competitive engineering culture. In fact, they were quite proud of it. To move into management, you were expected to embrace that. I guess it didn’t suit my style of working. By the time I was leaving I was definitely ready for something very different.

After a couple of years with some start-ups and a brief return to Microsoft, you joined Adobe. Did the culture there differ from Microsoft?

I joined Adobe in 2004 and stayed for 9 years. Adobe had a different feeling for sure. The company was already working in an agile way. They were trying out new ideas. But this only existed at certain levels of the company; as I moved through the hierarchy and began to interact with different parts of the organizational structure it became clear that this way of thinking was not true for the entire organization. I reverted back to the mode of singular change agent and I began to feel trapped.

What does the culture at Microsoft or Adobe differ from Spotify

The way Spotify works is not fixed, unlike Microsoft. When I joined Microsoft the company had 18,000 people, when I left it had 60,000. But nothing much had changed during that time, the company still operated in the same way. I felt a similar thing after nine years at Adobe. Of course at Microsoft there was always some interest in finding better ways to work but these were always individually-led initiatives. At Spotify, culture is a constant source of debate. Organizational thinking permeates the whole organization, it’s not just aspirational or some HR-initiative. The feeling of finding a better ways to work is omnipresent at Spotify. I have been at Spotify for two and a half years and it feels like an organizational culture lab, we are constantly running experiments. And importantly, we are doing this while building a strong product in a competitive environment.

What doesn’t work at Spotify?

Big projects can be challenging. Especially given our model of autonomous teams. When we changed our UI to the new dark look. In a traditional organization it would have taken a few weeks. It took us three months and we had to pull a bunch of our developers out of normal team structures. Very un-Spotify.

What is your attitude towards failure?

Failure is part of the life of a continuous improvement organization. Failure is punished at big corporations. They want to be innovative but this attitude forces staff to play it safe. One of my favourite quotes is from the film director Kevin Smith, “Failure is success practice.” I really believe that.

This whole Spotify structure seems a bit chaotic for a manager. How is it for you?

I just have to trust we hired the right people. I have to make sure they have everything they need to make good decisions. Teams don’t need to tell me about changes. They make those decisions. This chaos works for us, mostly.

What is your ultimate goal with this model?

We want people to be happy, to build careers at Spotify, to have a sense of ownership over what they do. We want the model to be adaptable and to encourage continuous improvement.

What companies do you admire?

I admire Automattic, GitHub and Medium. All those companies are doing interesting things. But of course, they are also small. It’s hard to imagine them scaling, but I would be intrigued to see what they do. I also think that Zappo’s leadership structure is interesting. I don’t think this could apply to us, but it is interesting none the less in terms of organizational culture.

What books can you recommend about company culture?

Daniel Pink’s “Drive” is a good read. As is Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience”. The Hard Thing About Hard Things and The Advantage I also like. Currently High Output Management is on my reading list.